When people talk about great nation-wide public transit systems, names such as Japan or Switzerland are often mentioned. In this article I will show what makes Switzerland’s network so unique and why it is has become so popular.

I would like to thank my friends Benoît and Dorian for the fruitful discussions that lead to this analysis.What is an integrated timetable ?

There are many ways to build a robust public transit system. In big cities1 around the world, you will find metro / bus / tram networks that have high frequency service, which means you don’t need to worry about a timetable because the metro comes every five minutes. To link the big cities, a few countries decided to extensively build out high-speed rail. So we have this high frequency service within densely populated areas, linked to other big cities by high-speed rail.

However more sparsly populated areas, when they do have public transit, often have irregular service or only peak-hour service (a few connections in the morning and a few connections in the evening). France is a perfect example of this: big cities like Paris, Marseille or Lyon have really good internal networks and they are all linked by high speed-train but when it comes to tiny or medium sized cities, the quality and frequency of the service drops sharply2.

Between high frequency service and sporadic service, there is the clock-face scheduling. If you want to connect A to B but can’t justify the costs of implementing a high-frequency metro system, you can define a regular service throughout the day which is always departing at the same times. For example a line that goes every 30 minutes could be scheduled at 6:15, 6:45, 7:15, 7:45, … This way, regular users of the system won’t have to think too much about the timetable but still get an acceptable level of service.

Switzerland implemented such a service and even took it further. The train lines between cities are scheduled about every 30 minutes, but they are synchronized in a way that you can smoothly take a connecting train or bus at a station without waiting too much. This is what I mean with the term integrated timetable. If you need to go from A to C via B, and for example the trip from A to B takes 10 minutes and the trip from B to C takes 20 minutes, then people wouldn’t probably use this route if the wait at B was 25 minutes because of a bad connection.

In this article, I will take a look at the publicly available data and analyse the Swiss timetable and public transit network.

Particularities of Switzerland

Density

It is no secret that Switzerland is a tiny country. The argument could be made that this country has good public transit because of its size, and that this is not applicable to larger countries. While Switzerland is quite densely populated (around 207 people / km²), it doesn’t have any big cities by international standards. Here is the list of the five most populated areas3:

| Name | Inhabitants | Metropolitan area |

|---|---|---|

| Zürich | 421,000 | 1,334,000 |

| Geneva | 203,000 | 579,000 |

| Basel | 178,000 | 541,000 |

| Lausanne | 140,000 | 409,000 |

| Bern | 134,000 | 410,000 |

Only 12.4% of the population of Switzerland lives in a Gemeinde (administrative limit of a city) with more than 100,000 inhabitants but almost 50% of the population lives in villages between 1,000 and 10,000 inhabitants 4. In this sense, Switzerland has a kind of a ‘village sprawl’, meaning that you will find a (tiny) village every few kilometers.

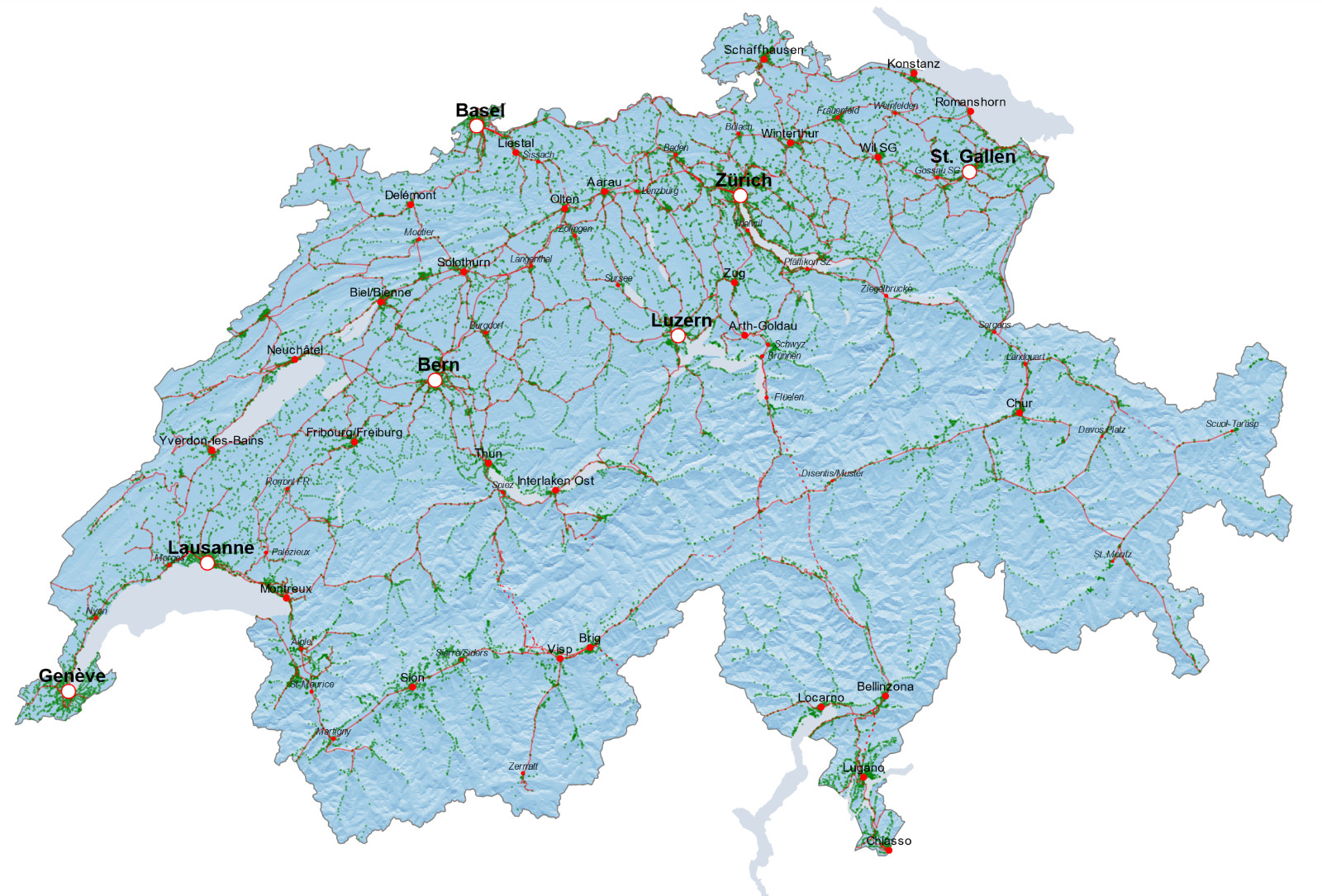

Terrain

The other caracteristic of Switzerland is that it is very mountainous. Even though most people live in the flatland (a flat region between the alps and the Jura mountain chain), Switzerland still has challenging terrain to build on5. Moreover the terrain is very expensive and the country can’t just build a new train line without spending billions. This means that regional and intercity trains have to mostly share the same tracks, which makes the system very sensitive to delays6.

Figure 3. Important cities, terrain and train network of Switzerland. Height map from ©swisstopo.

Figure 3. Important cities, terrain and train network of Switzerland. Height map from ©swisstopo.

Analysis of the Swiss public transit network 7

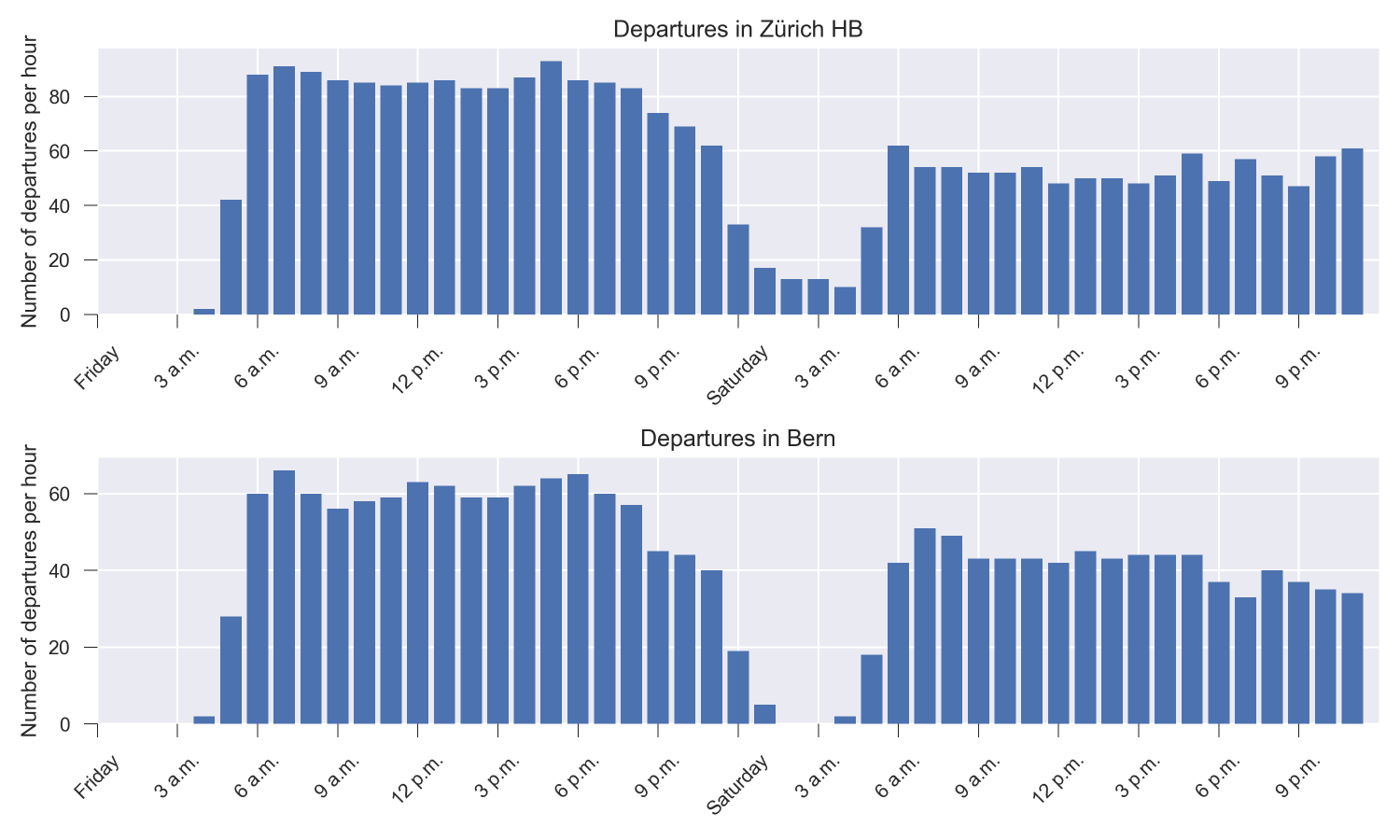

Switzerland has schedulded its network such that you could in principle go from somewhere to anywhere every 30 minutes throughout the day. The most prominent network is the train network (mostly owned by SBB CFF FFS, the national railway company), but there is also a myriad of other options, such as trams, buses, boats, funiculars, gondola lifts, rack railways, … which are all part of the timetable. Most cities in Switzerland do also have night service on the weekends8.

A pratical example of the integrated timetable

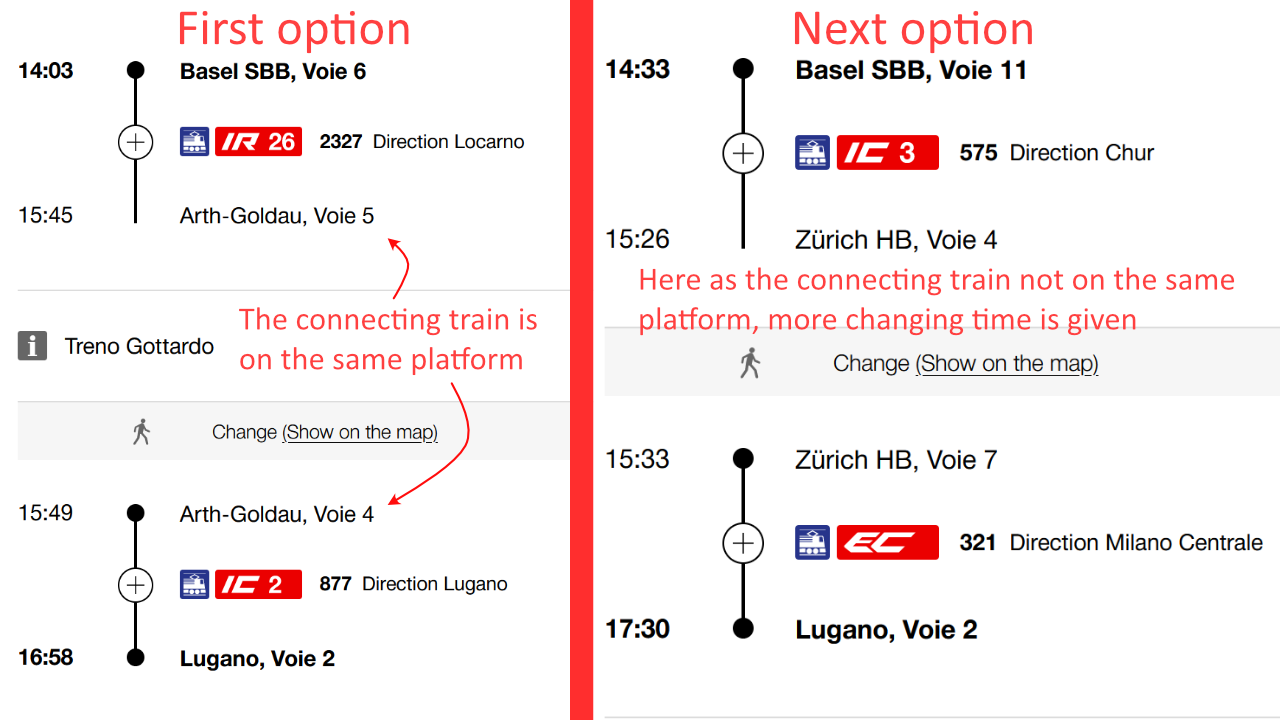

Let’s say that we want to go from Basel (north of Switzerland) to Lugano (through the alps, south of Switzerland) with the public transit system. Using the sbb website, on a random Saturday at 2pm, we can see the available options:

Here we see that indeed we have a connection every 30 minutes. But what is more interesting is that the direct train (without any changes) isn’t faster than the route with a change in-between.

Here we see that indeed we have a connection every 30 minutes. But what is more interesting is that the direct train (without any changes) isn’t faster than the route with a change in-between.

If we look more closely at the route taken by the first two trains:

Here both possibilities don’t even have the same route but do take the same amount of time. The 2pm train goes through Luzern and then Arth-Goldau to Lugano, and the 2:30pm train goes first to Zürich and then to Arth-Goldau (via Zug). In both cases, the changing time to the connecting train is not above 7 minutes.

Statistics on the whole network

Taking the gtfs data of the Swiss timetable for 20227, I simulated all possible trips from A to B in Switzerland by public transit. To reduce the number of calculations, I considered only train trips and limited myself on one particular day: Friday 1st, July 2022. I chose this date because it is a normal weekday but also because some lines that go all the way up on the mountains are only open in Summer.

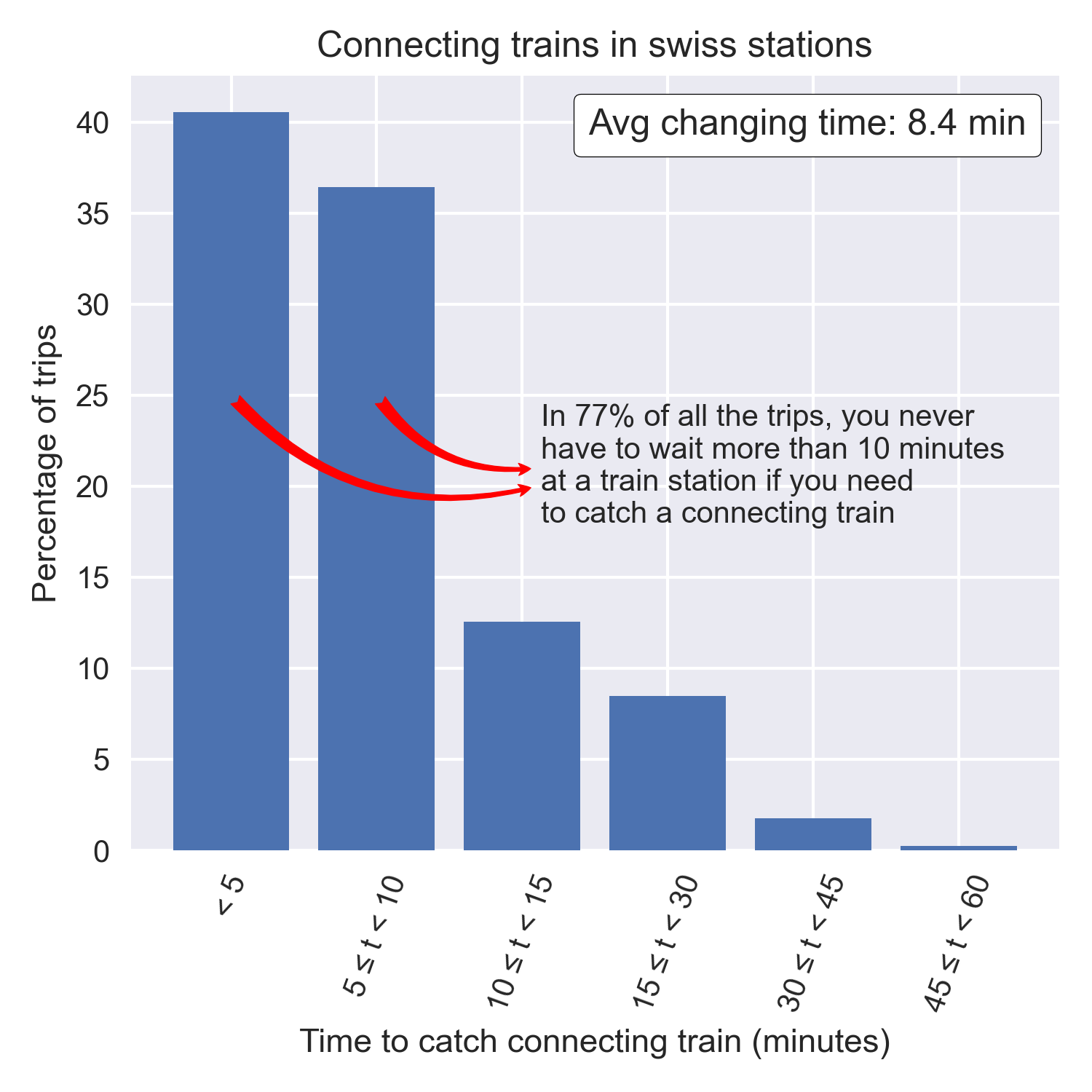

I started at every train station in Switzerland around 10am (to avoid the peak-hour bias), and then let the computer with a time-dependent bfs calculate all the best routes to every other station. With that, I had a complete graph of all the possible (train) routes that you can take in Switzerland. Then I took every station and looked individually at every path going through this station and calculated the time it takes to change trains. Here are the results averaged over all train stations in Switzerland:

Figure 4. Connection times for every possible trip in Switzerland

Figure 4. Connection times for every possible trip in Switzerland

Despite that every train is scheduled only every 30 minutes you never have to wait more than 10 minutes at any train station in the vast majority of all trips. This allows for smooth utilization of the network and reduces the overall time it takes to go from anywhere to anywhere. In fact, a study9 showed that over long distances, the Swiss prefer to take the train instead of the car, and this is probably due in part to the integrated timetable.

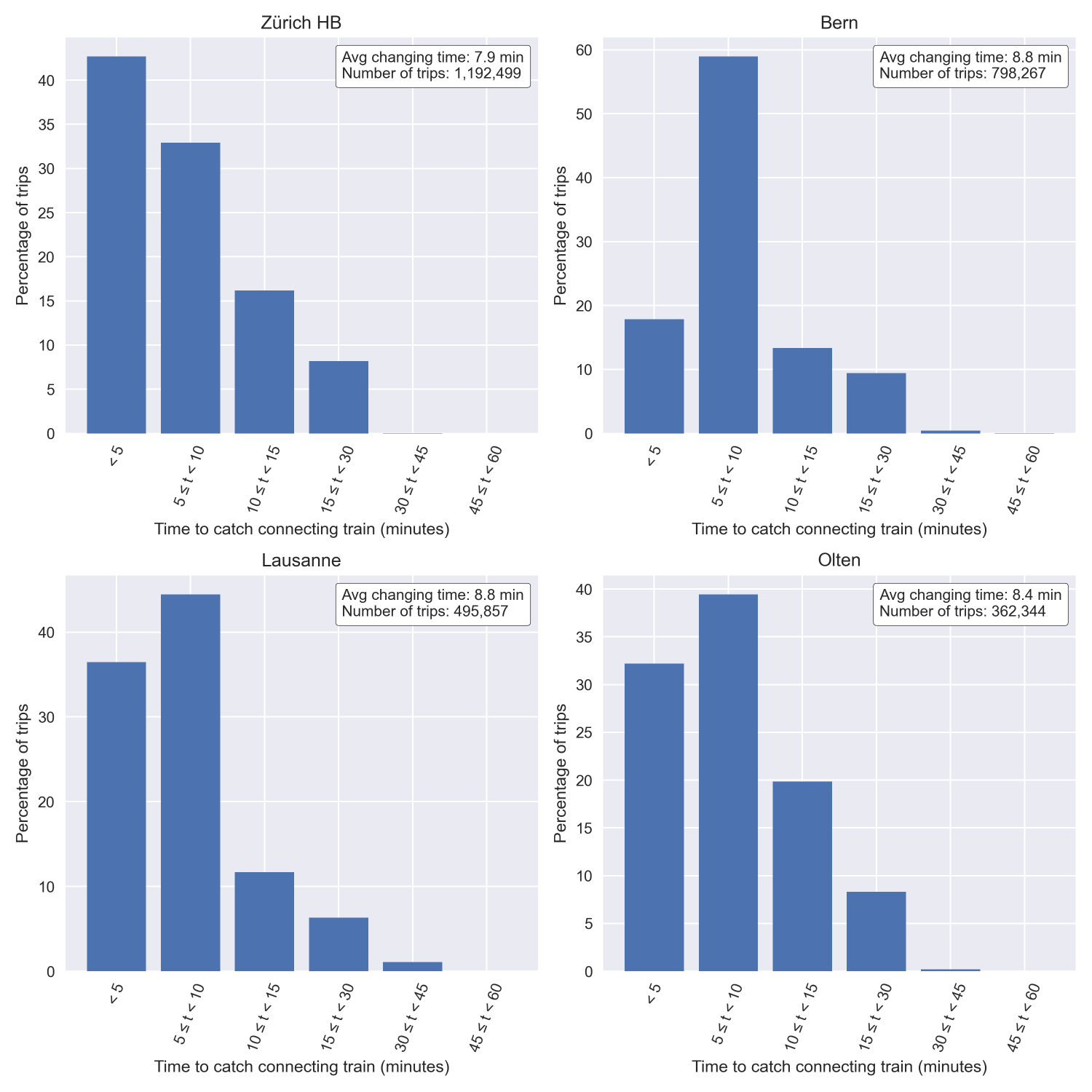

Figure 5. Changing time statistics on the four most connected stations of Switzerland.

Figure 5. Changing time statistics on the four most connected stations of Switzerland.

Figure 6. Departure statistics for the two busiest stations of Switzerland

Figure 6. Departure statistics for the two busiest stations of Switzerland

Reliability

A well synchronized timetable requires a reliable network. While not everything is perfect and perturbations on the network can happen, trains in Switzerland are generally on-time. Looking at the official statistics, we see that for 2021:

- about 92% of passenger trains were on-time

- about 99% of connections were guaranteed

The SBB company defines ponctuality as follows:

Train punctuality measures the percentage of all trains which are on time. A train is considered on time if it reaches its destination with less than three minutes’ delay. Connection punctuality measures the percentage of connections reached. In this way, SBB takes into account the fact that some passengers miss connections when a train has less than three minutes’ delay and is still counted as on time.

Accessibility of the network

The other factor to the success of the Swiss public transit system is that it reaches almost every village of the country, even the most remote villages in the mountains. This means that you can also take the trains and buses to go hiking and skiing. There is also a law in place that forces all public transit companies to accomodate for wheelchairs10.

On the following figure we see all the points reachable by public transport, where even low density villages in the mountains get access to the network:

Figure 7. Every stop (in green) of Switzerland ; it may be any kind of stop (train, bus, tram, boat, …)

Figure 7. Every stop (in green) of Switzerland ; it may be any kind of stop (train, bus, tram, boat, …)

Conclusion

Despite the mountainous areas and the village sprawl, Switzerland managed to implement a successful public transport network which is used by a significant percentage of the population10. Of course cars are still very prevalent in the country but a 2019 study9 showed that for long distance trips, trains are the prefered way of travel. Switzerland still continues to invest heavily in its public transport infrastructure11,12.

Discussions about this article:

- Hackernews: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=31807913

- Reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/dataisbeautiful/comments/vfuntc/oc_the_integrated_timetable_of_switzerland/

Not Just Bikes discussing this article in his video about Swiss trains:

More readings on the subject

Interactive maps

- Live map of the train network: https://maps.vasile.ch/transit-sbb/

- Interactive map of the future network: https://sbb-step2035.ch/en/passengers/

Articles

- The initial project of the integrated timetable: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rail_2000

- https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/to-the-second_the-swiss-timetable-is-due-to-meticulous-planning/34102496

- A more mathematical explanation on how to build an integrated timetable: https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/bitstream/handle/20.500.11850/155771/eth-49450-01.pdf

-

The definition of big is kind of loose here. I mean at least one million inhabitants. ↩︎

-

An example: Narbonne (~60,000 people) and Perpignan (~120,000 people), which are only 65 km apart, are linked by a (almost) hourly regional train, which stops service at 8 pm. Sometimes there is a irregular TGV linking the two cities. ↩︎

-

2015 numbers, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_cities_in_Switzerland ↩︎

-

Numbers taken from https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commune_(Suisse) ↩︎

-

But they love building tunnels. Switzerland appears eight times on this list and the longuest railway tunnel in the world is located in this country. ↩︎

-

Between A and B, every half-an hour, the fast trains (Intercity, stops only in ‘big’ cities) go first, then the fast regional trains (Interregio, RegioExpress, stops now and then) go and finally the little regional (S-Bahn, stops everywhere) to avoid overtakes. ↩︎

-

All the data used for the analysis here has been taken from https://opendata.swiss/en. ↩︎

-

The most impressive night network is Zürich’s, but I would give an honorable mention to Fribourg’s night network despite being a not so densely populated canton (biggest city here is Fribourg with 40,000 people). ↩︎

-

https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/aktuell/neue-veroeffentlichungen.assetdetail.17164643.html ↩︎

-

Law in question: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/2003/667/en. It is slowly being implemented throughout the country ↩︎

-

Future network: https://sbb-step2035.ch/en/passengers/ ↩︎

-

https://www.bav.admin.ch/bav/en/home/modes-of-transport/railways/rail-infrastructure/expansion-programmes.html ↩︎